Watch Out! There’s a Prrreet About!

If you need a diversion from the current lockdown, then can I recommend a new language website which will appeal to more than just readers of blogs about Words.

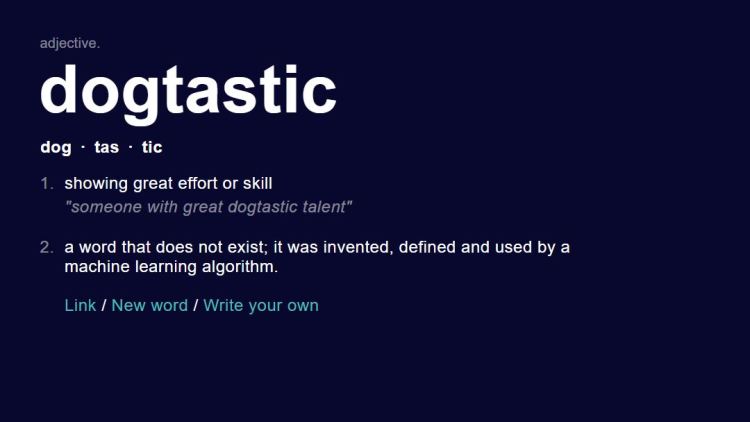

This Word Does Not Exist is the brainchild of Thomas Dimson, the former Director of Engineering at Instagram. It is an AI-based site which performs one very simple function – it uses AI and machine learning to offer definitions for words which are not real.

There are two main modes to it – in one, you can just keep clicking and allow the site to suggest random false words to you, with their plausible but still false meanings also offered up. In the more fun mode, you can type in your own made-up words and see what meaning the machine gives them.

I started seriously, with variations on ‘Stay Alert’, as I felt that there had been so much discussion recently in the UK about what this ambiguous piece of Government advice means that I might as well let a machine tell me:

Frankly, as a definition, it doesn’t make much sense, and it seems to confuse its adjectives and its nouns. Just as clear as Government advice then. So Perfect.

I then reminded myself that this is an escape from lockdown, rather than a way of continuing to worry about it. So I moved on to try to think of words which could exist but currently don’t. Pretty sure I will start to use this one in conversation soon:

And then finally, I just put in some random strings to see what the AI suggested:

I feel like I need to draw a picture of a Prrreet, go and hunt for one, check out museums and so on. It already feels like one actually exists.

I don’t think there is any risk with this website. People aren’t going to use it to claim that certain words really mean certain things. The definitions are generated automatically, there is a huge disclaimer on every page and nothing on here will ever appear on any formal dictionary page.

Instead it is a great deal of fun and a further illustration that not only does language constantly evolve, with technology at the centre of that change, but that words which may seem fanciful now could become standard usage in a few years’ time.